A new study published in the European Heart Journal says we should care about blood levels of a metabolite trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO), but is that true?

NBC News: Study explains how red meat raises heart disease risk

For starters, this was a well run and controlled study. Researchers randomly assigned 133 subjects to one of three isocaloric diets with the only difference being the presence of red meat, white meat, or vegetarian protein. Similar to the study by Dr. Ludwig that we referenced earlier, a strength of this study was that the study team supplied all meals for the subjects. Therefore, there was no guessing about what the subjects ate or if they complied with the recommendations. That makes this a strong nutritional study.

Subjects stayed on each diet for four weeks and then had a washout period before transitioning to the next diet. The main take home is that eating red meat increases the blood level of TMAO, which declines after four weeks off the red meat diet. As described in the article:

a red meat diet raises systemic TMAO levels by three different mechanisms: (i) enhanced nutrient density of dietary TMA precursors; (ii) increased microbial TMA/TMAO production from carnitine, but not choline; and (iii) reduced renal TMAO excretion. Interestingly, discontinuation of dietary red meat reduced plasma TMAO within 4 weeks.

It is important to note in our era of frequent conflicts of interest, NBC news reported that the lead investigator for the study is “working on a drug that would lower TMAO levels.” While that in no way invalidates the findings, it does legitimately raise suspicion for their importance.

Interestingly, the study did not test eggs, another food reportedly linked to TMAO. They did, however, note that increased choline intake, the proposed “culprit” in eggs, had no impact on TMAO levels.

The study also did not investigate fish. Fish, traditionally promoted as “heart healthy,” has substantially higher concentrations of TMAO than meat or eggs. One thought, therefore, is that high TMAO levels are produced by gut bacteria rather than the food itself. Although this is an unproven hypothesis, it would also explain variability among subjects.

Now for the harder question. Does any of this data matter? For this study to be noteworthy, we have to accept the assumption that TMAO is a reliable and causative marker of heart disease.

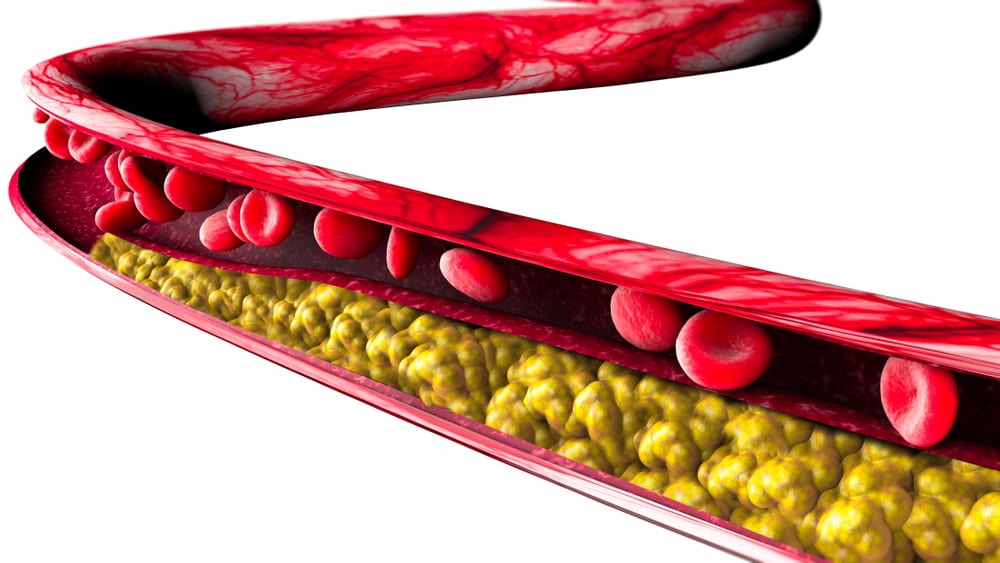

The main NEJM study linking TMAO to an increased risk of cardiovascular disease is not as conclusive as many promote. First of all, only those at the upper quartile of TMAO level had a significant increase in cardiovascular disease risk. Lower elevations had no significant correlation.

Second, those with increased TMAO and cardiovascular disease risk also were more likely to have diabetes, hypertension and a prior heart attack; furthermore, they were older, and their inflammation markers, including myeloperoxidase, a measurement of LDL inflammation, were significantly higher. With so many confounding variables, it is impossible to say the TMAO had anything to do with the increased cardiovascular disease risk.

This study in JACC that saw a correlation with TMAO and complexity of coronary lesions, also found an increased incidence of diabetes, hypertension, older age in the high TMAO group.

Finally, this study found no association at all between TMAO levels and increased risk of cardiovascular disease.

Based on these mixed findings, the jury is still out, and we have plenty of reason to question the importance of elevated TMAO as an independent risk marker or causative factor of coronary disease.

Most importantly, however, since multiple studies continue to show no significant association between meat and egg consumption and increased heart attacks or mortality risk (references here, here, here, here and here) the weak surrogate markers don’t seem likely to matter much. Don’t get caught in the minutiae. Focus on a real-food diet that helps you feel better and improves the vast majority of your markers. And if you have elevated TMAO, the studies suggest you should also check your blood pressure, blood sugars, and inflammatory markers as they may also be elevated. In my opinion, until we have much more convincing data on TMAO, you are far better off targeting those more basic parameters than a blood test of questionable value.

Thanks for reading,

Bret Scher, MD FACC

Originally Posted on the Diet Doctor Blog