What do I mean by “misunderstood?” Look no further than the common misnomer of “good” or “bad” cholesterol.

Good and Bad Cholesterol

While it may be true that High-Density Lipoprotein (HDL) has potentially beneficial functions (reverse cholesterol transport), we have to remember there is no such thing as good and bad cholesterol. The cholesterol carried by HDL is the same as that carried by LDL. The only thing that makes it good or bad is if it ends up synthesizing our hormones or bile acids (good), or if it ends up in our vessel walls (bad).

If it’s true there is no such thing as good and bad cholesterol, why do we care about our HDL levels?

First, let’s start with the basics.

HDL is the smallest and most densely packed lipoprotein and has one or more ApoA protein on its surface. HDL can help lipids move around in circulation by accepting triglycerides or cholesterol from other particles, thus helping a VLDL turn into an LDL, or helping an LDL contain less cholesterol (turning a small dense LDL into a less densely packed LDL).

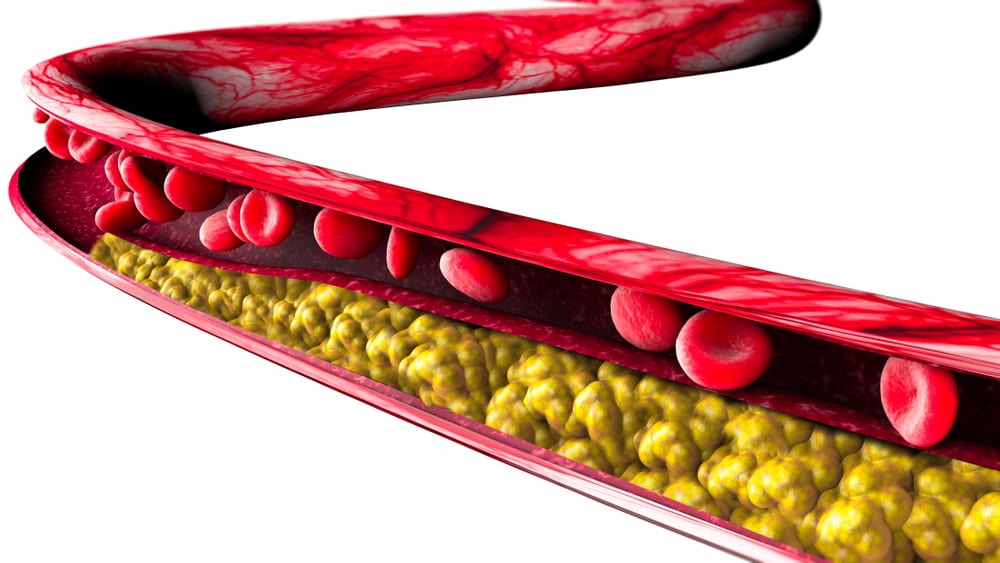

Like LDL, HDL transports cholesterol to the liver for recycling or excretion, or to the hormone producing cells like in the adrenals. Unlike LDL, HDL does not have the potential to get retained in the vascular wall and does not, therefore, contribute to plaque formation. In fact, functioning HDL can remove cholesterol from the vessel wall, thus putting it back into circulation and possibly removing it from the body.

Back to the question at hand.

Why should we care about HDL levels?

Early epidemiological trials showed that lower HDL levels were associated with a higher risk of cardiovascular disease and even death. With such a strong association, the medical profession promoted elevated HDL levels as protective and low levels as something we need to avoid.

Since these were observational epidemiological studies, they do not prove that the low HDL caused the problems, only that HDL was associated with it. For instance, HDL is also known to be low in diabetes, metabolic syndrome and insulin resistance. It may, therefore, simply be a marker of underlying metabolic dysfunction that contributes to increased risk. Yet, HDL’s function in reverse cholesterol transport, and its ability to remove cholesterol from vessel walls suggests a more direct impact on cardiovascular health.

It is also important to note that the Framingham data suggested that increased cardiovascular risk with elevated total cholesterol and LDL-C was lost in the presence of high HDL. In fact, very low levels of LDL combined with very low HDL levels had a much higher risk than markedly elevated LDL levels when combined with elevated HDL.

Thus, HDL proves to be a useful marker to help predict cardiovascular risk. For instance, one large meta-analysis showed that total cholesterol/HDL ratio was a much stronger predictor of cardiac mortality than total cholesterol alone.

In addition, the PURE study, an observational trial in over 135,000 subjects, showed that when considering lipid changes brought about by nutritional changes, ApoB/ApoA1 (essentially LDL-P/HDL-P ratio) is the best predictor of clinical outcomes.

Thus, HDL level is important in assessing cardiovascular risk.

Drugs Muddy the Picture

While HDL may be a good predictor of risk, raising it with drugs does not seem to confer added benefit.

For instance, cholesterol ester transferase protein inhibitors (CETP inhibitors) significantly reduced LDL by 20-30% and increased HDL 100-fold, yet showed either no clinical benefit or even worse, an increased risk of death.

This was a shock to many in the lipid world as the notion of “good” and “bad” cholesterol would clearly predict lowering LDL and raising HDL would confer dramatic health benefits. So much so, that multiple pharmaceutical companies invested hundreds of millions of dollars developing these drugs only to abandon them when the trials showed no benefit.

Part of the issue is that not all HDL lipoproteins function the same. There are subsets of people with genetically determined markedly elevated HDL levels who have an increased risk of CVD. They may have plenty of cholesterol circulating in HDL particles, but the HDL particles are dysfunctional and therefore do not effectively remove cholesterol from vessel walls or LDL and do not effectively transport it to the liver. Conversely, there are those with a specific genetic mutation called ApoA1 Milano who have very low HDL-C and lower cardiovascular risk.

Simply measuring the HDL cholesterol content, therefore, may not accurately reflect its function. While we do not have easily available tests to measure HDL function, we can potentially use HDL particle assessment as well as the company it keeps (i.e. low triglycerides, larger less dense LDL particles) to better assess the potential benefits of HDL. Thus, if there is any concern about potentially dysfunctional HDL, I usually recommend advanced lipid testing to see the specific subtypes of HDL.

What can we conclude from all the HDL confusion?

Raising HDL with drugs does not reduce cardiovascular events, yet having a naturally low HDL is associated with increased risk.

The best answer, therefore, is to live a lifestyle that helps you have a “not low” HDL level. This means first and foremost avoiding the medical conditions associated with low HDL (i.e. insulin resistance, diabetes, and metabolic syndrome).

Textbooks predictably state the interventions to naturally raise HDL include exercise and moderate alcohol intake. Unfortunately, these have minimal effects. In fact, they pale in comparison to a low carb high fat lifestyle. In my 20+ years in the medical field, I have never seen an intervention as effective as LCHF in raising HDL, and the studies agree.

This brings us back to our question once again.

Why are HDL levels important?

HDL levels are important because it is a reflection of our underlying metabolic health and our lifestyle. A properly constructed LCHF lifestyle lowers triglycerides, raises HDL, and reduces the small dense LDL, among other benefits. Such a lifestyle likely reduces overall cardiovascular risk and will likely be shown to improve longevity and health span. While HDL may not be the main reason for this, we can’t ignore its role simply because it is more nuanced than “good” and “bad” cholesterol.

My advice, therefore, is to see the whole picture. Embrace the nuance. And make sure you get a thorough and proper evaluation of your cardiovascular risk.

If you are hungry for more, I created my Truth About Lipids program, a program focused on Cholesterol, to help break through the confusion and provide you with everything you need to thoroughly understand cholesterol and its impact on your health.

Learn more: Truth About Lipids Program

If you still have questions, you may want to consider a one-on-one health coaching consultation so you can get the individual attention you deserve with a thorough assessment of your lifestyle and its impact on you as an individual.

Please comment below if you have any questions or comments that may help further the discussion.

Thanks for reading.

Bret Scher MD FACC