Work With a Doctor Who Really Gets It

Looking for a more individualized approach to your health? Confused about how all the contradictory health advice applies to you? Looking to break free from our failing healthcare model? We have you covered.

Request a medical consult from Dr. Scher today!

Let’s Talk

Send us a message and let us know how we can help you.

Consult With Dr. Scher

The initial consultation is $1,495. Contact Dr. Scher today to see if you qualify.

You can take charge of your health.

Let Dr. Scher show you how.

Let’s Talk

Send us a message and let us know how we can help you.

Meet Dr. Scher, MD

The Low Carb Cardiologist

Hi, I’m Dr. Scher, and I’m changing the direction of preventive cardiology to better serve more people like you with the care you deserve. I’m also the CEO and Lead Physician at Boundless Health and the Low Carb Cardiologist. I spent the past 15 years as a frustrated board-certified cardiologist. My patients weren’t achieving their optimal health, and I didn’t have the time or resources to guide them. That’s why I sought out additional certifications in lipidology, nutrition, personal training, functional medicine, and behavioral change.

It is through this specialized training and working with thousands of patients I recognized how to provide better care. Your health is too important to trust to guidelines designed for the ‘average’ person. You are not average, nor should you want to be!

I’m glad you’re here. It tells me you know you deserve better care. I can’t wait to get started finding your path to true health.

Bret Scher, MD FACC

Board Certified Cardiologist and Lipidologist

Yes, People LOVE Dr. Scher’s Approach

Dr. Scher’s one-on-one Consultation was extremely valuable in my search for advice about cardiovascular health on a low-carb diet. During our discussion, I learned that interpreting lab results using the standard reference ranges can be misleading for anyone on low-carb or keto. He helped me better understand my test results and develop effective strategies to improve my cardiovascular health through nutrition and exercise. Dr. Scher is a good listener and a pleasure to work with. He is an excellent preventive cardiologist with a deep understanding of lipidology and metabolism, and the issues and challenges specific to a low-carb lifestyle.

Gabriel B.

We hear the words Heart Healthy a lot, especially when it comes to our nutrition.

By now, you’re likely used to seeing cereals with the “heart healthy” moniker. Is it really heart healthy? We all too frequently refer to foods as “heart healthy”, or we say that our doctor gave our hearts a “healthy” checkup.

It all sounds nice. But what does it mean? How do we define heart health?

How does LDL Cholesterol affect Heart Health?

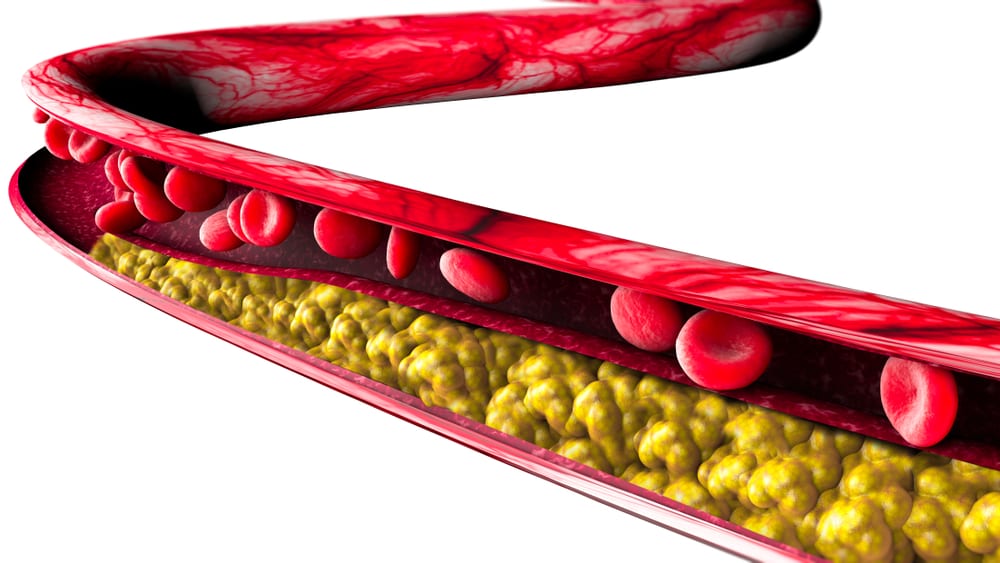

Unfortunately, most of our current definitions center around LDL cholesterol concentration. While LDL cholesterol plays a role in heart health, it by no means defines heart health in totality.

In fact, in many cases it is the least important factor.

Our healthcare system has simplified things too much, so as a result we focus on one bad guy, one demon to fight. In reality heart disease is caused, and made more likely to occur, by a constellation of contributing issues.

Elevated blood sugar, elevated insulin levels, inflammation, high blood pressure, poor nutrition, and yes, lipids all contribute to heart health. It does us all an injustice to over simplify it to one single cause.

What food is heart healthy?

Our superficial definition of cardiac risk is how industrial seed oils containing polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) became known as “heart healthy.”

Studies show that they can lower LDL. But they can also increase inflammation and have no clinical benefit and even increase risk of dying. According to our simplified definitions, that doesn’t stop them from being defined as “heart healthy.”

That’s right! Something that increases our risk of dying is still termed “heart healthy.” How’s that for a backwards medical system?!

Same for blood sugar. If you have a diagnosis of Type 2 Diabetes (DM2) that is a risk for cardiovascular disease. If you don’t have the diagnosis, you are fine. That ignores the disease of insulin resistance that can predate diabetes for decades and increases the risk of heart disease and possibly even cancer and dementia.

Cereal can also be called “heart healthy” as they may minimally lower LDL. But is that a good thing if they contain grains that also worsen your insulin resistance and metabolic syndrome? I say definitely not.

Time has come to stop this basic, simplified evaluation and start looking at the whole picture.

How Low Carb High Fat Diets Improve Heart Health

Low carb high fat diets have been vilified as they can increase LDL. But the fact of the matter is that it does so only in a minority of people. The truth is that they can improve everything else!

These diets reduce blood pressure, reduce inflammation, improve HDL and triglycerides, and reverse diabetes and metabolic syndrome! Shouldn’t that be the definition of “heart healthy” we seek? Instead of focusing on one isolated marker, shouldn’t we define heart health by looking at the whole patient?

Only by opening our eyes and seeing the whole picture of heart healthy lifestyles can we truly make an impact on our cardiovascular risk and achieve the health we deserve.

Join me in demanding more. Demand better.

Thanks for reading,

Bret Scher, MD FACC

Don’t look now, but the updated clinical practice cholesterol guidelines from the American College of Cardiology, the American Heart Association and others are getting personal. Although the guidelines still contain their familiar approach — that I consider too aggressive with drug therapy — the latest 2018 version of the guidelines now includes an impressive update to emphasize lifestyle intervention, plus a more individualized approach for risk assessment.

MedPage Today: AHA: Revised Lipid Guide Boosts PCSK9s, Coronary Calcium Scans

Could this be the start of a progressive trend away from shotgun statin prescriptions? I sure hope so.

Prior guidelines emphasized the 10-year ASCVD risk calculator as the main determining factor for statin therapy. In the 2018 update, the guidelines acknowledge that the calculator frequently overestimates the risk in those individuals who are more involved with prevention and screening. (In other words, those patients more interested in and proactive about their health; I find many in the low-carb world fall into this category.)

The ensuing discussion with a healthcare provider should then focus on:

[T]he burden and severity of CVD risk factors, control of those other risk factors, the presence of risk-enhancing conditions, adherence to healthy lifestyle recommendations, the potential for ASCVD risk-reduction benefits from statins and antihypertensive drug therapy, and the potential for adverse effects and drug–drug interactions, as well as patient preferences regarding the use of medications for primary prevention… and the countervailing issues of the desire to avoid “medicalization” of preventable conditions and the burden or disutility of taking daily (or more frequent) medications.

I appreciate the attention the new guidelines bring to the depth of the discussion that should ensue between doctor and patient. Considering the treatment burden is equally as important as the burden of disease, and possibly even more important in patients who have not been diagnosed with heart disease, these individualized discussions about trade-offs are critical to personalized care.

Also worthy of mention is the increased use of coronary artery calcium scores (CAC) to help individualize risk stratification. The updated guidelines specify CAC may be useful for those age 40-75 with an intermediate 10-year calculated risk of 7.5%-20%, who after discussion with their physician are unsure about statin therapy. They specify that a CAC of zero would suggest a much lower risk than that calculated by the ASCVD risk formula, and thus take statins off the table as a beneficial treatment option.

This is huge. I cheered when I read this! I have been critical of prior guidelines that focused on ways to find more people to place on statins. The mention of finding individuals unlikely to benefit from statins is a giant step in the right direction.

The guidelines go even further: they mention that a CAC either over 100 or greater than the 75th percentile for age increases the CVD risk and the likely benefit of a statin. A CAC between 1-99 and less than the 75th percentile does not affect the risk calculation much and it may be worth following the CAC in five years in the absence of drug therapy. I would still argue that a CAC >100 does not automatically equal a statin prescription and we need to interpret it in context, but I greatly appreciate this attempt at a more personalized approach.

The guidelines also go beyond the limited risk factors included in the ASCVD calculator by introducing “risk modifying factors” such as:

- Premature family history of CVD

- Metabolic syndrome

- Chronic kidney disease

- Chronic inflammatory conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis and psoriasis

- Elevated CRP > 2.0 mg/L

- Elevated Lp(a) > 50 mg/dL or 125 nmol/L

- Elevated triglycerides > 175 mg/dL

Although they use these criteria to define an increased risk, the opposite would likely hold true. An absence of those criteria could define a lower risk situation.

Some changes deserve mention from a controversy standpoint as well. For instance, the new guidelines recommend checking lipid levels as early as two years old in some circumstances. Two!

They also recommend statin therapy for just about everyone with diabetes with no mention of attempting to reverse diabetes before starting a statin, a drug that has been shown to worsen diabetes and insulin resistance. In addition, the new guidelines do not mention the likely discordance between LDL-C and LDL-P in those with diabetes.

Last, the new guidelines define an LDL-C > 190 mg/dL as an absolute indication for statin therapy with a treatment goal of 190 mg/dL is in familial hypercholesterolemia populations (and even then has heterogenous outcomes). There is a clear lack of data supporting that same recommendation for metabolically healthy individuals with no other cardiac risk factors and no other characteristics of familial hypercholesterolemia. This is a clear example of when a guideline turns from “evidence based” to “opinion based.”

In summary, the guideline committee deserves recognition for its emphasis on an individualized care approach, its use of CAC, and its broader description of discussing potential drawbacks of drug treatment. It still combines opinion with evidence and believes all elevated LDL is concerning, but I for one hope it will continue its progression away from generalizations and someday soon see that individual risk variations exist, even at elevated LDL-C levels.

Thanks for reading,

Bret Scher MD FACC

Originally Posted on the Diet Doctor Blog

Despite what the sugary beverage and processed snack food companies want us to believe, all calories are not created equal.

A new study from Harvard shows that individuals following a low-carbohydrate (20% of total calories) diet burn between 209 and 278 more calories per day than those on a high-carbohydrate (60% of total calories) diet. So the type of calories we eat really does matter.

The New York Times: How a low-carb diet might help you maintain a healthy weight

This isn’t the first study to investigate this topic, but it is likely the best.

The current study was a meticulously controlled, randomized trial, lasting 20 weeks. Even more impressive, the study group provided all the food for participants, over 100,000 meals and snacks costing $12 million for the entire study! This eliminated an important variable in nutrition studies — did the subjects actually comply with the diet — and shows the power of philanthropy and partnerships in supporting high-quality science.

After a run-in period where all subjects lost the same amount of weight, participants were randomized to one of three diets: 20% carbs, 40% carb, or 60% carbs, with the protein remaining fixed at 20%. Importantly, calories were adjusted to stabilize weight and halt further weight loss, thus making it much more likely that any observed difference in calorie expenditure was not from weight loss, but rather from the types of food consumed.

After five months, those on the low-carb diet increased their resting energy expenditure by over 200 calories per day, whereas the high-carb group initially decreased their resting energy expenditure, exposing a clear difference between the groups. In addition, those who had the highest baseline insulin levels saw an even more impressive 308-calorie increase on the low-carb diet, suggesting a subset that may benefit even more from carbohydrate restriction.

Why is this important? It shows why the conventional wisdom to eat less, move more and count your calories is not the best path to weight loss. Numerous studies show better weight loss with low-carb diets compared to low-fat diets, and now studies like this one help us understand why.

Our bodies are not simple calorimeters keeping track of how much we eat and how much we burn. Instead, we have intricate hormonal responses to the types of food we eat. It’s time to accept this and get rid of the outdated calories in-calories, calories-out model, thus allowing for more effective and sustainable long-term weight loss.

Originally Posted on the Diet Doctor Blog

Here it is again. The term “healthy” connected as a descriptor.

We see it all the time. Healthy Whole Grains. It reminds me of the common use of “fruits and vegetables,” as if they are one in the same.

Are whole grains, by definition, “healthy?”

For a full, in depth description, see the Whole Grains Guide on Diet Doctor, where I was the medical editor and reviewer.

For the quick answer, let’s leave it as a “maybe.”

If you choose to eat refined grains, white flour, processed snack foods, in essence the Standard American Diet, then switching to whole grains will almost certainly improve your health. And that is where the majority evidence in favor of whole grains stops. Compared to refined grains, they are great.

Who should eat whole grains?

If you are insulin sensitive, live in a society where you are physically active for most the day, eat fewer calories than most industrialized nations, and maintain a healthy body weight, then whole grains can be a healthy part of your diet. Observation of the Blue Zone countries demonstrate that whole grains can be part of a healthy lifestyle in that setting.

We cannot, however, extrapolate those findings above to apply to all Americans, Europeans, Asians etc. and say whole grains are by definition “healthy.”

Who should not eat whole grains?

If you are metabolically unhealthy with diabetes, metabolic syndrome or insulin resistance (estimated to be 88% of all Americans), then whole grains are anything but “healthy.” Borrow a continuous glucose monitor for a day and see how your blood glucose responds to whole grains. If you aren’t perfectly metabolically healthy, it isn’t pretty.

Instead, if you eat a whole-foods, low carb diet without grains and sugars, then whole grains have no necessary role and no association with health.

Enjoy the more detailed guide from DietDoctor.

Thanks for reading,

Bret Scher, MD FACC

START A CONVERSATION

Connect with Dr. Scher to see if you qualify for the consultation.

Let’s Talk

Send us a message and let us know how we can help you.